Islamic Institutions and the Challenges of Revival Featured

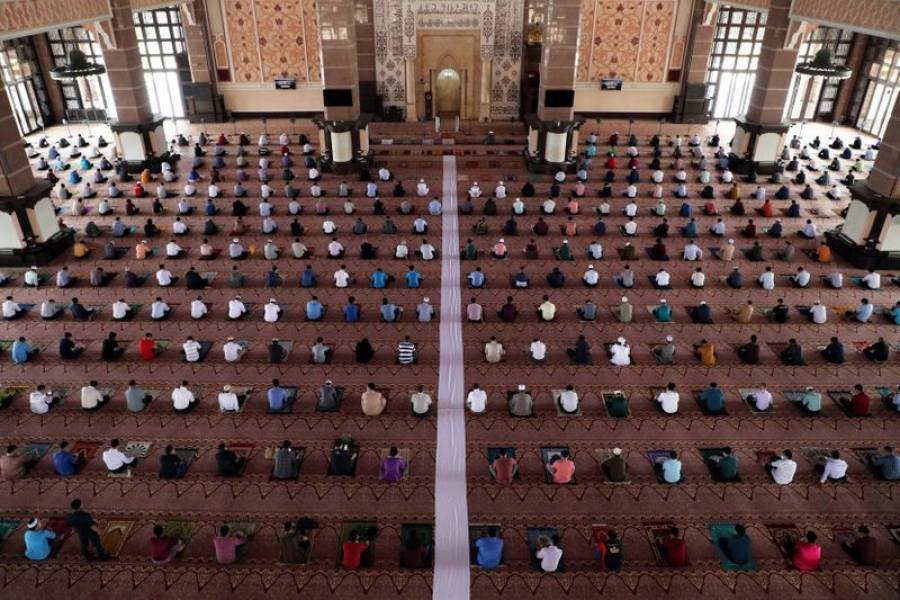

Islamic institutions are spread throughout the expanse of the Ummah, expanding as it expands, diversifying as its needs diversify—confirming that the Ummah has not fallen short in establishing and inaugurating Islamic institutions, nor has it overlooked their vital role and significance. So, where then lies the problem?

The tangible impact of these institutions is weak and meager, nearly nonexistent—save for the minimal relief provided by some aid organizations to the desperate! Where is the role of scholarly associations, academic unions, clubs, forums, syndicates, societies, and other institutions? Why do we always feel abandoned, without a guardian to protect us or an advocate to defend us? How do we navigate life’s paths without a guide or a seasoned navigator, stumbling blindly and plunging recklessly into challenges? Undoubtedly, there is a flaw stemming from accumulated shortcomings that have now become major challenges demanding confrontation. What are these challenges?

Independence: The First and Greatest Challenge

Scarcely any institution on this planet is fully independent. Yet most global institutions enjoy varying degrees of independence, expanding or contracting—that grant them some margin of freedom. In our Islamic world, however, independence is rare, besieged, and stifled to the point of suffocation. Why?

Two reasons:

First, excessive control and dominance exercised by ruling regimes. Second, Muslims’ complacency with the bare minimum—merely securing governmental approval to establish Islamic institutions and allowing them to operate without obstruction, regardless of their effectiveness. Over time, these institutions gradually become tools of the regime, offering it grand services in exchange for meager benefits. For example, a scholarly body might serve as a facade to polish the regime’s image and lend it religious legitimacy in exchange for sporadic conferences with mercury-like titles, sponge-like content, and impacts as hidden as guarded eggs—locked away in drawers tighter than the cells of tyrants.

This pattern pervades most activities. To confront this challenge, resistance and perseverance are needed to carve out spaces of independence, which, through persistence, can solidify into reality.

The Absence of Institutionalization Within Islamic Institutions and Its Peril

If Allah Almighty decreed in the Quran that it guides to the straightest path, and if the "straightest path" for establishing and managing institutions is institutionalization—and if Islam, with its comprehensive law, governs all spheres of life—then we affirm that institutionalization is a core feature of Islamic institutions. But before delving into this critical topic: What is institutionalization?

Institutionalization in work, management, and administration means that all institutional activities follow legally established foundations, rather than being dictated by individuals. This rational human behavior is termed "institutionalization" (derived from the Arabic root "أسس," meaning "to establish"), as the foundation (*asās*) is the cornerstone of any structure.

We begin our journey with institutionalization in Islam from the central, indispensable point: education that molds personalities inclined toward institutionalization. No matter how stringent laws and regulations are, they remain ineffective unless individuals are shaped to embrace institutional work. This requires cultivating psychological, emotional, and conceptual traits that form the inner core of a person joining an institution.

Personalities dominated by whims, ego, worldly desires, or the twin vipers of greed for wealth and power are detrimental—especially if such traits prevail in a society. Institutional work then becomes endangered, teetering on the edge of collapse. No laws, regulations, or institutional legacies can salvage this unless rooted in moral integrity.

Hence, the Quran provides teachings and guidance to protect society from destructive ethical, social, and administrative diseases. It condemns whims (*hawā*) more harshly than the idols it came to demolish. As discerning scholars noted: "No deity worshipped besides Allah is more detestable to Him than whims." The Sunnah elaborates on Quranic principles through words, actions, and education, inherited generationally. Countless Quranic verses, prophetic traditions, and scholarly exhortations—even their exemplary conduct—reflect inner purity and self-restraint surpassing all expectations.

Moving to the immediate circle surrounding this core, we find education in the elements constituting the spirit of institutionalization: consultation, collectivity, specialization, impartial accountability, gentleness, obedience within legal bounds, rule of law, rejection of nepotism and tribalism, prioritizing truth over personalities, constructive dialogue, and devotion to truth. Without these, institutional work collapses into personalization of decisions, projects, and management.

The Necessity of Harnessing the Ummah’s Potential

Every nation harbors diverse talents, potentials, and aptitudes. A mature, conscious Ummah succeeds in unearthing these potentials and integrating them into its multifaceted endeavors. The harder questions are: How do we identify talents? How do we deploy them appropriately? Yet the toughest question is: Are we ready to explore our landscape with liberated, impartial methodology? Are we willing to move beyond complacency to seek competence? Do we possess the courage and sincerity to transcend partisan or group loyalties and embrace the Ummah’s vast horizons, granting opportunities to the qualified and allowing the Ummah to benefit from its scattered talents? It is time to break free from closed cocoons into the Ummah’s open expanse.

Diversity, Inclusion, and Rightful Affiliation

What matters is not mere affiliation or securing opportunities, but ensuring that opportunities align with recipients’ capabilities. We must abandon favoritism, nepotism, and shoehorning relatives or friends into positions for which thousands of more qualified Muslims exist—individuals specialized, talented, and aptly suited for roles in charity, academia, media, advocacy, politics, or service. Diversity of talents is Allah’s gift to humanity. Some scholars interpret the prophetic saying, "The differences in my Ummah are a mercy," as referring to diversity in professions and talents. Exceptional leaders and societies place each member in their rightful place, as the Prophet (peace be upon him) did: he did not entrust the banner of jihad to Abu Huraira, Mu‘adh, or others unsuited for it, nor tasked Khalid, Hamzah, or Zayd ibn Harithah with scholarly roles—a precedent followed by the Rightly Guided Caliphs.

These are the foremost challenges. I do not claim exhaustiveness here, but offer a diligent effort that calls for more. May those who see room for addition not withhold their contributions from the Muslims. And Allah is the source of strength.